How to Make a PR Crisis Worse

One of the most enduring truths in public relations is that crises rarely erupt out of nowhere. More often, they are made worse by the decisions that follow.

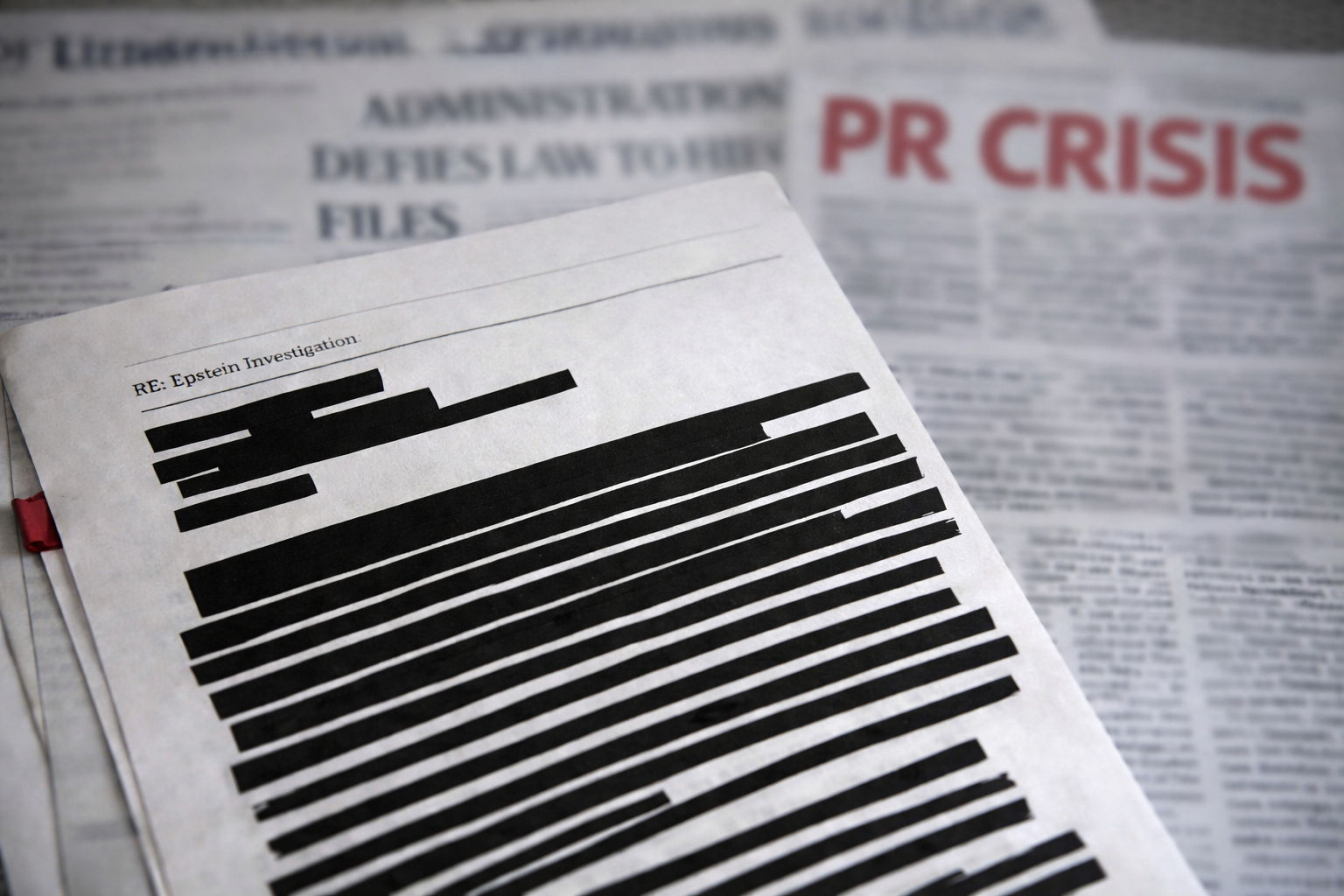

In December, the Trump administration handed Democrats an unexpected gift just as the 2026 midterm narrative was taking shape. Ordered by Congress to release the Epstein files, the administration released roughly 10 percent of the documents, heavily redacted, with little new information revealed. The decision not to fully comply with the order quickly became the story itself.

From a communications standpoint, it offers a textbook example of how to prolong and deepen a crisis rather than resolve it.

First, the partial release triggered immediate negative coverage from major news organizations, with critics framing the decision as a failure to follow the law. That framing gave political opponents a clear, repeatable talking point that will now likely resurface well beyond the current news cycle.

Second, by withholding information, the administration ensured that the Epstein files would remain a live issue heading into the 2026 midterms and potentially into the 2028 presidential election. In crisis communications, longevity is often the enemy. The longer an issue lingers, the more opportunities it creates for renewed scrutiny, speculation, and political weaponization.

Third, the episode violated one of the most basic rules of crisis management. Do not let bad news dribble out. Partial disclosures invite follow-up reporting, leaks, and continued investigation. They also undermine credibility, making every subsequent statement subject to heightened skepticism.

The irony is that this crisis was entirely avoidable. The files have existed for years. Had they been released earlier, the issue might have faded into the background. Instead, the delayed and incomplete disclosure kept the story alive and amplified its impact.

This is not a new lesson. Political history is filled with examples of how efforts to conceal or manage the truth often backfire. From Watergate to impeachment proceedings involving Presidents Clinton and Trump, the pattern is consistent. Attempts to obscure facts tend to expand the damage rather than contain it. In many cases, forthright disclosure early on would have resulted in far less lasting harm.

For PR practitioners, the implications are clear. During a crisis, everything said will be fact-checked, dissected, and compared against prior statements. Misleading reporters or withholding information almost always guarantees prolonged negative coverage. Trust, once eroded, is difficult to restore.

It is also worth remembering a principle I articulated decades ago and that still holds true today. There is no one-size-fits-all crisis communications plan. Every crisis demands original thinking, tailored to the facts, the stakeholders, and the broader context.

As attorney Ty Cobb, who led the Trump White House’s response to the Russia investigation, told The Wall Street Journal, the handling of this episode reflects a lack of coordinated messaging and accountability. Multiple voices speaking at once, each protecting their own interests, rarely leads to effective crisis management.

The takeaway for communications leaders is simple but often ignored. Transparency, timing, and discipline matter. When those elements are missing, even manageable situations can spiral into enduring reputational damage.